Utopia Has Teeth

Or, How to Become Someone Else (and Why It Doesn’t Work)

There are people who go to the edge of the world because they cannot bear the nearness of others. Then there are people who go because they cannot bear the nearness of themselves.

The dense, unmoving weight of the heat sat on the skin like another layer of clothing. Volcanic dust clung to sweat, to boots, to the hems of skirts, to the cuffs of trousers. The ancient smell of sun-baked rock and salt, and something far more pervasive and pungent: goats. Always the goats, wandering without hesitation or shame through the settlements, as though they were the original inhabitants and everyone else merely passing through.

This was the stage chosen by a handful of idealists in the late 1920s and early 1930s, people who came with wildly different visions of what a new life might mean.

Floreana Island, Galápagos.

Not strictly speaking uninhabited. There had been settlements before, but all had failed. In the 1800s, whalers and pirates used the island as a watering stop. In 1832, Ecuador claimed the Galápagos and attempted to colonise Floreana. They built a prison colony, which later collapsed due to starvation and brutality.

Later, a short-lived farming settlement failed due to drought and isolation.

By the early 20th century, Floreana was considered haunted by misfortune. “The cursed island”, with only 1–2 local families living there intermittently.

No infrastructure.

No town.

No trade.

No medical care.

No way off the island without the luck of occasional visitors at sea.

This is where the film Eden is set.

Those who don’t know the story of the European settlers who tried their luck here in the late 20s and early 30s, I guess I could say this essay will be full of spoilers. However, it was probably never the filmmakers’ intention to surprise anyone with unexpected turns of events or a novel ending, so if you don’t know much, or anything at all, you might as well start here.

For all the elements of the film that reviewers have found problematic, I believe it might not always be the point in a historical drama to present events as they were, not even as they have been handed down to us through the interpretations of people who were there to experience and witness it all.

As Gabriel García Márquez put it with absolute to-the-point genius, “Life is not what one lived, but what one remembers and how one remembers it in order to recount it.” This applies very much to the memoirs of the survivors of the Galapagos Affair. How they remembered, as well as the extent to which they were able to own up to the truth, versus the ways in which they might have edited it.

Another way I would rephrase this quote — one that keeps surfacing and resurfacing in my life in all sorts of situations — is that life events and our memories of them are not archives but interpretations. The essence of life is not formed from events as they happened, but from the narrative we have made of them. Unless we have it on film, we have no access to our lives as it was yesterday, or at any given time. We only have what we remember and how we remember.

As for Eden, the makers of the movie obviously had things to say, which they have woven into real events that happened to real people. So, while the story as they told it is somewhat historically inaccurate, I have found no problem with the artistic license they have taken.

And these are some of the thoughts that have been tumbling around in my head in the last few weeks, since I saw Eden, and my own struggles to endure the noise of civilisation have resurfaced.

Nietzsche In Boots

Dr Friedrich Ritter.

The first settler came to Galápagos with his companion and lover, Dore Strauch, from a Germany in transition, a world already cracking at the edges. Nietzsche’s ideas had filtered into the culture as a kind of spiritual dare: become the one who stands apart, who makes himself.

The First World War had shattered certainty; the Weimar years loosened old moral structures without providing anything stable in their place. Berlin was full of artists, mystics, political radicals, and people reinventing themselves at high speed. The old world had ended, but the new one was not yet formed.

Hitler was a rising but not yet inevitable force. The feeling was not yet terror, but instability. A sense that ordinary life was no longer bearable for anyone with a sensitive inner life.

Ritter, a physician with philosophical ambitions, believed that society had become weak, distracted, and spiritually diluted. He read Nietzsche not as literature but as instruction, and convinced himself that the only path to authenticity was to leave civilisation altogether, to build a life from pure will, discipline, and thought.

Floreana, to him, was not paradise. It was a stage on which to prove that a human being could become self-created and uncompromised, even if the rest of Europe were collapsing behind him.

Dore Strauch, Friedrich Ritter’s companion, had been a former student of his in Germany. This was not the clichéd story of the ageing professor and his much younger student. Ten years her elder, Ritter, in his mid-thirties, was the visionary, the theorist, the architect of the experiment. Dore was the follower, the believer in his vision, a woman willing to abandon her life to enter his world.

Dore had been married, but Ritter had persuaded her to leave her husband and follow him to the then uninhabited Floreana in 1929. They intended to live as a kind of philosophical experiment: vegetarian, self-sufficient, free from the moral decay of Europe.

Her health was fragile, though. She suffered from multiple sclerosis, chronic pain, and permanent exhaustion. This made her dependent, emotionally and physically, in a context that demanded brutal autonomy.

And Ritter, the self-sufficient ascetic, became impatient with her weakness, resentful, increasingly cruel in small ways. There was no open violence, but clarity and detachment so cold it could cut.

The island magnified both of them: Ritter’s discipline turned severity. Dore’s loyalty turned isolation.

The Idealists Who Weren’t Supposed to Make It

Ritter was there to prove a point. He arrived not simply to escape society, but to demonstrate that the Übermensch could be forged, that the philosopher could become the “new human” by stripping away the world.

And then, the Wittmers arrived and ruined that narrative the moment they stepped off the boat. They didn’t come to build an image or find purpose. Working class, ordinary, untheorising, with almost nothing to their name, not even an ideology, (with Frau Wittmer heavily pregnant), no one would have expected Heinz and Margarete Wittmer to make it through the first season. Least of all Ritter, who deliberately gave them a patch of land further away from the main stream, one he considered impossible to cultivate. He literally sent them to live in a cave, fully expecting that they would give up and leave him and Dore to themselves within months.

But the Wittmers had not moved to Floreana to prove anything. They were moving away from hyperinflation, from wages worthless by lunchtime, from savings erased overnight, from hunger and riots and extremism on all sides.

They did not speak about transformation, purity, or the new human. They came because Margarete was pregnant and, having lost two babies already, grief had followed them too closely in Germany. They stepped onto the island, looked at the ground, the heat, the distance to water, and began to work. While the others philosophised and wove dreams, they were already repairing the cistern.

They were the kind of people who did not need a story to live.

While Ritter and Dore were trying to transcend humanity, the Wittmers, through painstakingly hard work and patience, built a shelter. They carried water. They built a garden. They sent letters to their family and requested small supplies, built relationships with the crews of passing ships, the Ecuadorian Postmaster and Officials in Puerto Ayora.

Local officials, who often disliked European eccentrics, respected the Wittmers. They were polite. They didn’t claim to be better than anyone. They didn’t write manifestos.

And small favours accumulated.

The Wittmers slowly built a liveable little world for themselves.

The Diva Without an Audience.

So here they were on a cursed volcanic island. A Nietzschean physician, attempting to forge the Übermensch with his partner and a quiet German couple, who simply wanted their baby to live, when more people arrived.

Baroness Eloise Wehrborn de Wagner-Bosquet.

Born, Eloise Wehrborn.

German.

Cabaret performer, small-time actress, possibly a courtesan, spiritual teacher, salon hostess.

Married several times to men of status and wealth – none of them barons.

She arrived not to escape civilisation. Not to survive. Not to prove a point. But to become nothing less than a legend.

And, unsurprisingly, she didn’t arrive alone.

The Empress of Floreana, whom she declared herself on arrival, brought a harem of two men.

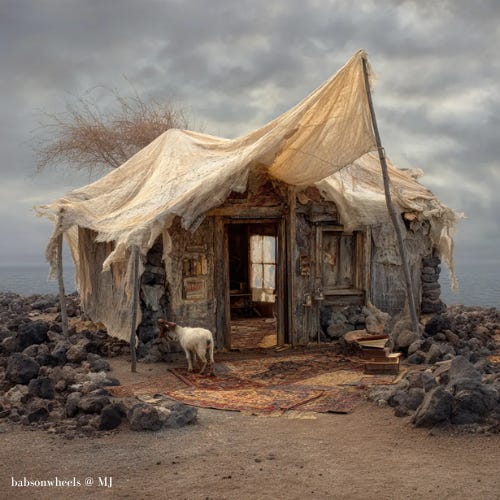

In the film, the men pull up a tent with rugs, furniture, books and a gramophone. Truly, this is glamping 1930s style. Why, I would happily move in!

Reality was a bit less glamorous, though.

They settled about half an hour’s walk from the Wittmers. Hacienda Paradiso, as she called it, was a makeshift shelter of timber, bamboo, and canvas salvaged from earlier failed settlements and from shipwreck detritus with a tent-like roof, a small table, and a few bits of furniture they’d brought or bartered from passing ships.

She decorated it with mirrors, fabrics, and a few books, trying to make it look like an exotic salon. She had a gramophone, which she liked to play, as she posed for visitors, reading aloud and playing records.

Rudolf Lorenz, German merchant seaman, was soft-spoken, emotionally dependent, and psychologically fragile.

He did not have the temperament for hardship, hunger, or chaos. He was not built for volcanic rock and erratic personalities. He grew exhausted, frightened, and mentally unsteady. He became the weakest person in the triangle, and therefore the one most likely to break.

Robert Philippson had a harder, more forceful, more aggressive personality. Possibly a former soldier or adventurer. Austrian. Coarse charm; physically confident; controlling tendencies. He was the Baroness’s enforcer.

Coming from an empire that had already collapsed, he was trying to rebuild a world where he could be important again. The island gave him a place where force still meant something. He would be the strong man beside the mythic woman. He enjoyed the idea of a lawless environment where he could be dominant—the strong man by the side of a mythic Empress.

It was a power triangle:

The Baroness needed to be adored.

Philippson needed to be powerful.

Lorenz needed to be wanted.

But for the Empress of Floeana, this was not enough. She was a colonial monarch; she needed subjects—or rivals—not neighbours.

You couldn’t even make this up. In this day and age, to our thinking, how could two grown men have fallen for this?

But apparently, history doesn’t care about plausibility, and the Baroness had grand plans. She wanted to build a luxury holiday resort. Not that they ever even came close to laying a foundation. The garden failed. “Hacienda Paradiso” was more performance than farm, and they were too consumed by quarrels to keep the garden alive or haul enough fresh water.

They began to take supplies from the other settlers.

The Baroness called it sharing; the others called it theft. Her men crept down the paths at night to carry off fruit, chickens, whatever could be eaten. It wasn’t hunger alone that drove them; it was her belief that rules were meant for lesser lives.

Lorenz was the servant-devotee. He cooked, fetched water, and endured her moods. The longer they stayed, the more those roles hardened. When his health failed, Philippson grew cruel, and the Baroness’s temper turned theatrical and violent. Lorenz was beaten, forced to sleep outside, and sometimes denied food. The Wittmers, their nearest neighbours, took pity on him and offered him shelter when he escaped for a few days at a time. The Baroness treated his departures as betrayals and then lured him back with promises.

Darwin in a Dinner Jacket

Allan Hancock, wealthy American businessman, oil magnate, patron of the arts, owner of a luxurious research yacht called the Velero III., had visited Floreana multiple times, supplying goods and filming the settlers. He had known Ritter before the Wittmers and the Baroness ever arrived.

A man of science and adventure, part explorer, part philanthropist, part showman, he did not flee from anything or need an identity rehaul. Hancock had the means to live exactly the kind of life he wanted, wherever he wanted.

With connections to Hollywood, Hancock loved stories. He filmed a silent “mock movie” with the baroness acting as the star — a pirate queen drama, playing herself as the queen of Floreana, and she fully believed that she would become a film star. But Hancock didn’t film her because he thought she had any special talents. He filmed her because he filmed them all. The baroness gave him drama. Ritter gave him philosophy. The Wittmers gave him respectable pioneering simplicity.

Hancock was often the only adult in the room, the one person who wasn’t hypnotised by the Baroness’s charisma or drawn into the ego-wars.

He was observant, pragmatic, and not entangled sexually or emotionally. He was wealthy enough not to need anyone’s approval, and socially powerful enough not to be intimidated. He had everything he needed. He could see clearly.

The Vanishing Acts

One morning in March 1934, as Margarete Wittmer later wrote, the Baroness came to their house “radiant with excitement,” saying she and Robert Philippson had been invited aboard a friend’s luxury yacht headed for Tahiti, and that they were leaving immediately, without time for farewells.

And this was strange, because no yacht was ever seen. No ship was recorded in the area. The Wittmers had seen no ships, and the view from their homestead allowed them to see every vessel approaching.

They left all their belongings behind, including clothes and personal items nobody would abandon. Only Lorenz spoke of the departure after that, and his story changed.

After that day, the Baroness and Philippson were never seen again by anyone, anywhere in the world.

Within days, Lorenz began adding or removing details:

Sometimes he said the yacht arrived in the morning, sometimes near dusk.

Sometimes he said he saw the Baroness wave goodbye, other times he said he only “heard” she had left.

Sometimes he said he helped her pack, sometimes he said she took nothing.

He changed which items she supposedly took: clothing, letters, nothing at all, and none of it was adding up because the Baroness’s favourite dresses were still hanging, her jewellery and expensive fabrics were still in her hut. Her weapons were still there. Philippson’s boots, rifle, and tools were left exactly where he had last dropped them. There was no sign of packing, haste, or preparation.

You don’t get on a yacht to Tahiti and take no personal belongings.

Lorenz then became agitated, evasive, frightened, even paranoid. He also began sleeping at the Wittmers’ house, because he was terrified to stay alone at Hacienda Paradiso.

Lorenz, already half-mad from fear and fever, begged the Wittmers to help him leave Floreana. In the end, he convinced a Norwegian fisherman, Nuggerud, to take him to Santa Cruz to find a ship home.

Weeks later, both men’s bodies were found mummified on the desolate island of Marchena, far off their route, their boat wrecked. To this day, no one knows whether they died of thirst, heat, or violence, and there was nothing left to prove how they had ended up there.

Hancock came not as a supplicant but as a witness. He was not a refugee. He arrived in safari boots and a scientist’s notebook, and what he saw unsettled him: the cheerful myth of paradise unravelled into theft, fear, and bodies. In late 1934, he sailed his yacht Velero III to Marchena Island, where the two missing men lay mummified, and wrote in the Los Angeles Times that the deaths were “unquestionably” not accidents.

Much of this essay is based not on the film but on what we know about the actual events. However, strangely, one of the things that stays with me most is something from the film which, based on everything we know about Ritter, probably never happened.

Ritter’s big breakthrough in the film is that Nietzsche, as well as Christianity, puts humanity above animals, but he has come to believe that our animal instincts (”we fight, we hunt, we f*ck, we kill”) are our inner truth and the essence of life. That as a species, we have spent thousands of years running from our true selves. While this doesn’t add up to anything we know about Friedrich Ritter, it resonated with me because it would have actually been the single most realistic conclusion for him to reach.

He never changed his worldview, though. He died still believing he had been right. That Nietzsche had been right.

He died of food poisoning, having eaten spoiled chicken (which they resorted to due to hunger). In the film, it was strongly implied that Dore had deliberately given it to him. We don’t know this, though.

Dore later suggested in her memoirs that he ate it deliberately as self-punishment.

The Wittmers implied he refused help, out of pride.

Others think Dore may have withheld help.

Still others think the Wittmers let him die.

But the real horror is not murder. The real horror is people living in close quarters, needing each other to survive, resenting each other, and eventually choosing not to save each other. Death by neglect. By pride. By silence.

The Baroness had called it love, but on Floreana, love had to carry water and dig for shade. One man enforced her will, the other worshipped her until worship became humiliation. By the time the heat broke that strange triangle, she and her favourite had disappeared into the Pacific without a trace, and the faithful one lay beside a stranger on another island, dried to bone and salt.

And the islands keep no records. They only keep the rumour.

When Dore sailed back to Germany, the story everyone remembers — the Baroness, the lovers, Ritter, the diaries — was already over.

Only the Wittmers stayed. The people who were never supposed to make it. The only people who survived the island were the ones who did not need to be extraordinary, but steady, ordinary, practical, undeluded by their own importance.

Heinz Wittmer, Margret Wittmer, their son Rolf, who was born on the island, and eventually a second child, Ingeborg, who was also born there.

The Wittmer children grew up to become guides, boat operators, and naturalists. And eventually, they established their own tourist lodge, the Wittmer Hotel, which their descendants continue to run to this day.

And the Wittmers’ descendants live on Floriana to this day.

Today, Floreana has a few dozen residents, a small primary school, one main road, one bar, and one church.

The volcanic cliffs are still there.

The tortoises and the goats are still there.

The water is still scarce.

The light is still harsh.

The silence is still profound.

And no one is trying to build Eden, or be a prophet, or a queen anymore.